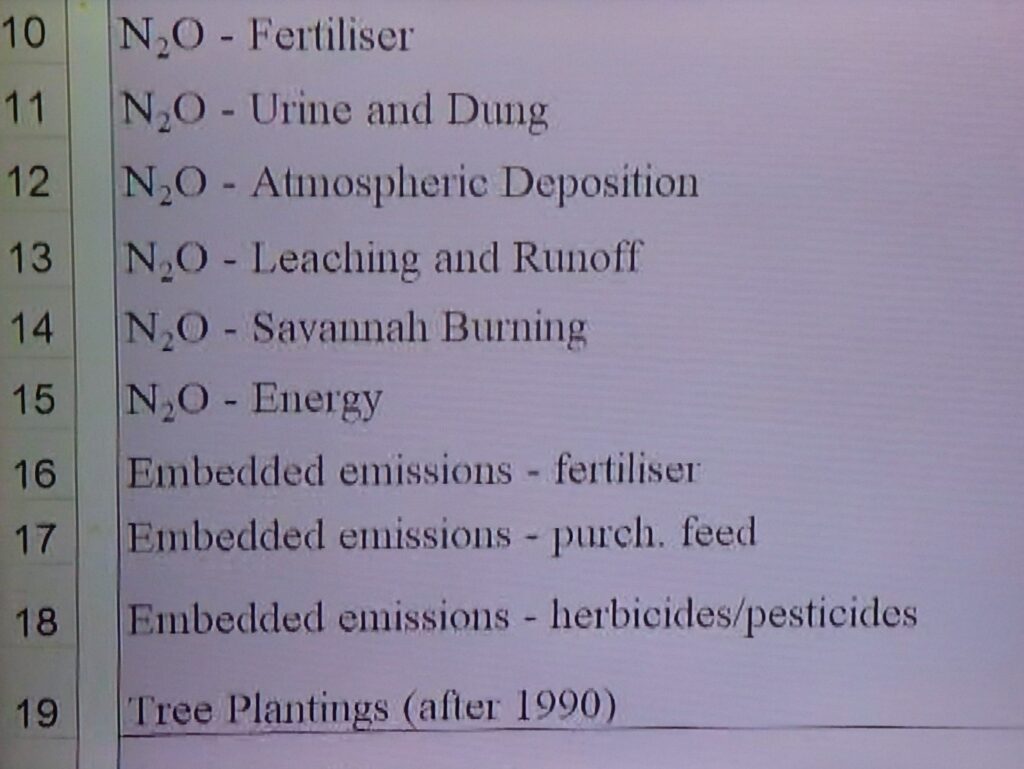

Carbon sequestration puts carbon into soils. Australia has the most number of soil carbon projects, the most innovative approach to issuing /measuring carbon credits for carbon sequestration. The projects aim at taking as much as possible greenhouse gas or carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. Methane from cattle burping production is the number one source of greenhouse gas emitted worldwide. It stays in the atmosphere for about 12 years. Listen that emitted by both fossil fuels but potent. Agriculture will pull carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere part of Australian government pledge to be carbon neutral by 2050.

How is it done, and what is in it for farmers?

It is what they are growing in that is the focus – soil health

Harry Youngman – Tiverton Agriculture Fund. (Borung Dja Dja Wurrung community)

Their properties have olive tree orchards; also table grapes, stone fruit and two dryland cropping operations in canola, wheat, barley, legume crops – chickpea and sorghum.

“It is what they are growing in that is the focus – soil health, differing crop rotations, less turning of the soil and replacing fertilizers with home-grown fertility inputs,” says Harry.

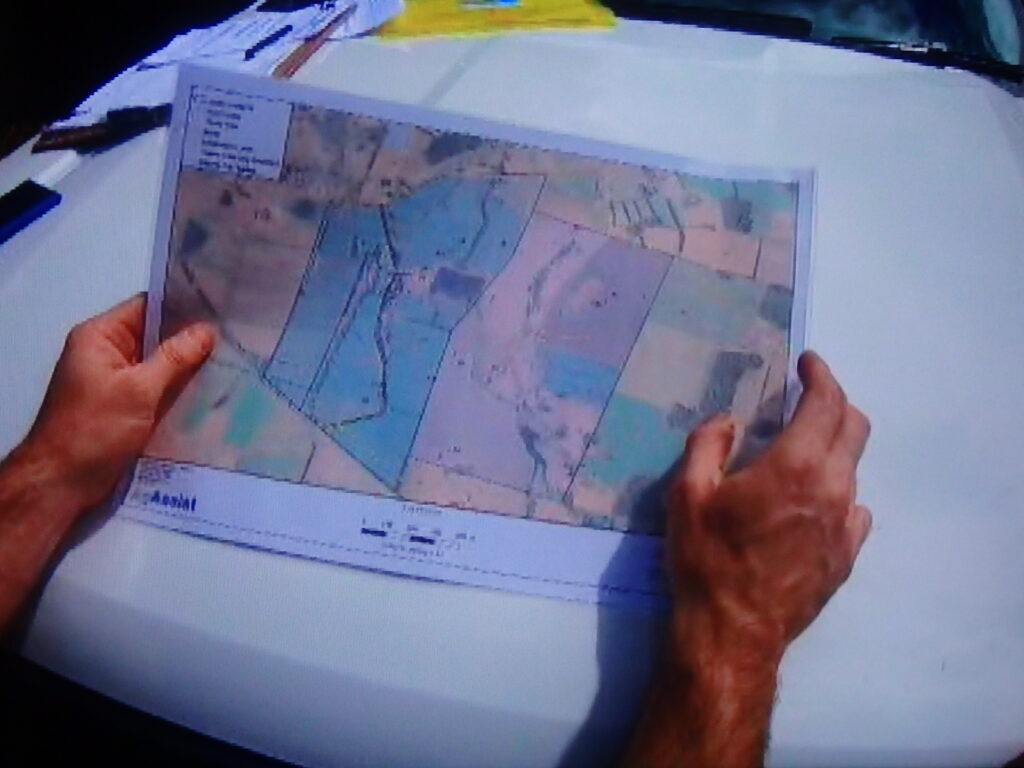

Auditable process must have excellent farm records, for 10 years minimum; Items, livestock counts, fuel imports, fertility inputs. The project registered with the Australian government Clean Energy Regulator. Having set a base level carbon in its soil at 2019 its first audit is done in 2024.

“Looking at the trees growing above ground which is slow, to expect the carbon levels to grow in the ground any quicker is wishful thinking. Slow, long, steady process that very cumulative process, anticipating they’re going to shift the percentage more than 1% over 10 years.”

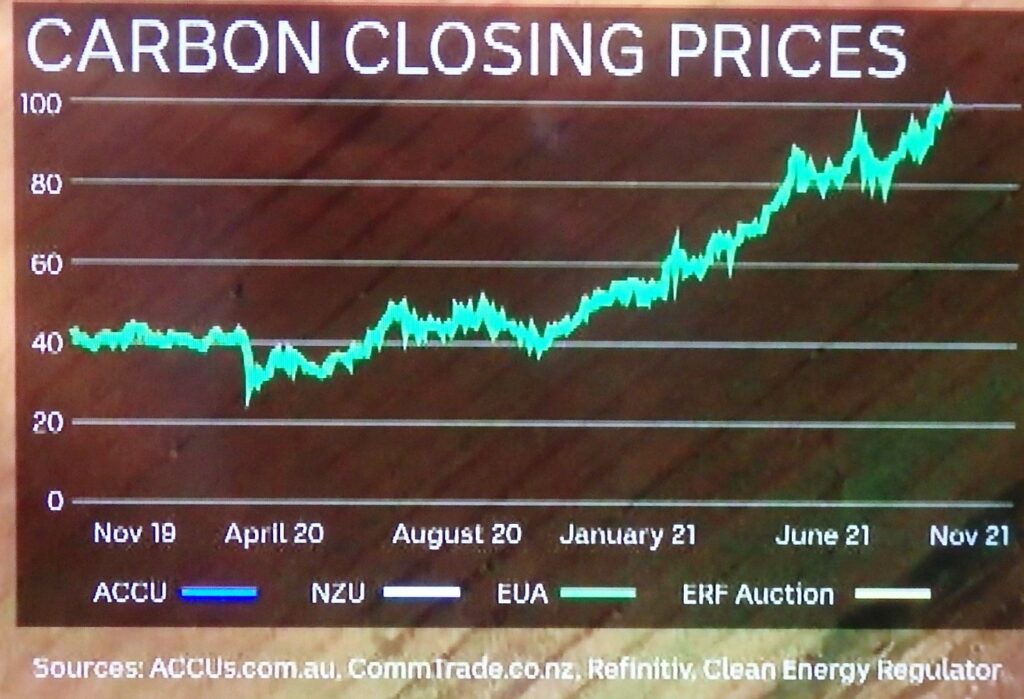

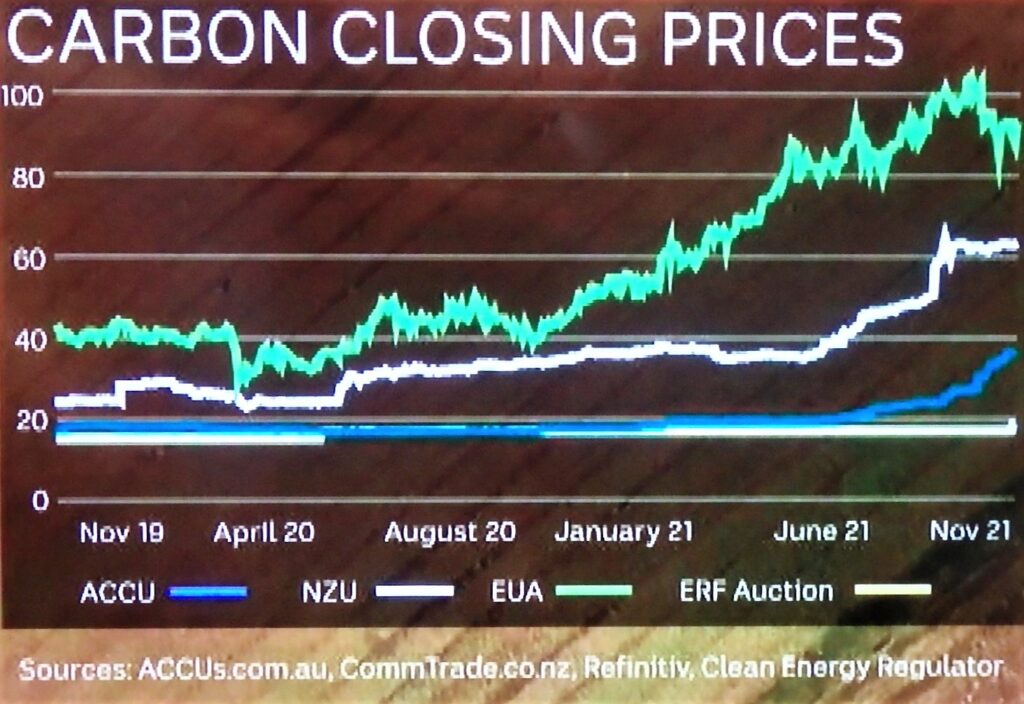

If Harry can prove but they have increased the carbon level above what was already in the soil well his farming methods he will be able to claim tradable carbon credits. One credit for every net tonne of carbon dioxide equivalent that is abated. At about AU$49 in December 2021, up from $16 per ton at the start of the year.

Matthew Warnken, Soil Carbon Project Developer.

“Farmers absolutely can make money from soil carbon. He develops solar projects for farmers to register and trade in the Australian carbon market. Farmers are emerging as price makers not price takers.”

The first soil carbon project was registered in 2015, it took five years for the first 50 so carbon projects to get onto the ERF but in the last 18 months that has grown fourfold.

The methodology for making carbon credits from soil is arguably the most administratively dense, most technically complex and the most costly method for getting carbon credits issued in Australia.

“Australia has 9 million hectares of agricultural land,” says Angus Taylor, federal Emissions Reduction Minister, “a very significant carbon sink.”

“The amazing thing about absorbing more carbon,” Shayleen Thompson, Clean Energy Regulator, “it is a way of reducing carbon emissions. It actually sequesters the carbon from the atmosphere into the soil. Which is why you can get carbon credits.”

To get more farmers involved in the carbon market, the government is relying on soil testing becoming a lot cheaper, and a new methodology. A set of rules to help farmers get built-up carbon in their soil and get carbon credits. Methods include; changing stock rotations retaining crop stubble rather than burning off, making irrigation systems more efficient, and using forested land to sequester more carbon. Land owners are encouraged to build soil carbon, diversifying their farm, improving the productivity and operations, and making the property more resilient to droughts.

Also an opportunity for consultants as last heard they’ll charge farmers thousands to sign up to the scheme. “Complexity agents, help farmers participate in the scheme and deal with the paperwork and administration if the farmer decide they cannot manage it period,” said Ms. Thompson

PM Scott Morrison says, “Australian farms could offset as much as 17 million tonnes of CO2 equivalent by 2050, generating $400 million for farmers in the process.” The ERF is not the only way they’re turning carbon into a commodity.

Stuart Austin, runs the McLeod family owned Wilmot Cattle Company. “It has been measuring carbon content across its farms for years. 2013 to 14 management changed from set stopped operation to a much more intensive rotation, longer rest periods. That is when we saw a real shift in the organic carbon levels and other component nutrients. It has always been part of the mix,

Wilmot base lined its carbon across two properties with the ERF in 2016. The ERF is the gold standard, but most expensive and most rigorous to participate in. It would not recognize the gains in carbon made prior to signing up to base-lining. We wondered if we had seen the big shift and had missed that opportunity, had not been able to capitalize.”

With Toby Grogan, Stewart investigated other carbon market options.

“Guys from the Regeneration Network in the U S said they could do something with the data. Using satellite imagery and Wilmot soil data it said it could prove the soil carbon had increased. Quite a debate about the rigor of it, the integrity of it, and did we think it would stack up to the court of public opinion.” Wilmot took the deal to the market and software giant Microsoft announced it paid $500,000 to the company for the carbon it had sequestered in the period 2017 to 2020.

By the time they took the methane emissions which equated to 10 or 12,000 tons of NH 4 over three years on the two farms. That brought them back to 43,000 tons of CO2. Because the carbon was purchased by a U.S. company, the amount will not be counted in the Australian target.

Before the end of the decade the National Farmers Federation (NFF) wants $5 billion of the farm gate income to be generated by ecosystems services. Tony Mahar NFF, stated “The soil carbon is not the silver bullet that will reduce emissions or become a total income stream for farmers. But what it can do is to be part of the solution. What we need is more methodologies and more practices for farmers to engage in that process.”

“Arguably producing the most nutrient dense grass fed beef.” Stuart Austin went on to say, “If we can improve souls by even 1% across land our farmers manage, that will give a profound productivity benefit and an abundant revenue stream, producing just as much food as in the past, and it will make a significant contribution national account offsetting global emissions.”

Indigenous Australian aboriginals have an ancient method

Traditional burning practices prevent raging fires that fill the atmosphere with tones of carbon. Carbon abatement programs have been running in northern Australia for many years. Kristy O’Brien journalist on Tiwi Islands were the Arafura and Timor Seas converge lie the Tiwi isles (Ratuati Irara – two islands).

Satellite image of the Tiwi Islands, Bathurst, Melville and Australian mainland Northern Territory (left to right)

Willie Rioli Ranger Supervisor with duties including controlling weeds, feral and bushfire controls. Northern Australia’s tropical savannas are amongst the most fire prone ecosystems on earth with up to half of them including the Tiwi islands prone to bush fires. Uncontrolled fires can destroy sacred sites, biodiversity, infrastructure and cause major environmental damage. Willy supervises from the air at the ranger burning program.

They plan to cover large tracts of land to drop fire and making sure burning is dispersed and effective. Ancestral knowledge is applied to reduce the severity of hot uncontrollable fire in the Goonapendri – the dry season steps in September. Spot fires help maintain the open vegetation structures that Savannah plants and animals evolved in. Being aware when cover plants and grasses are ready to burn these cool burns are expensive practices in remote areas like these.

The Tiwi rangers have found ways to monetize the burning. Looking at carbon, most emissions are generated from uncontrolled fires that sweep through remote parts of the islands from late August that produce greenhouse gases that threaten biodiversity. Reducing the extent of fires represents an opportunity to earn carbon credits.

“It is not only about earning money it is about looking after your country, looking after the animals and birds and bush tucker,” said Willy.

The deal was struck with Epex Gas Company four years ago. A relationship can be made between indigenous interests and the mining sector. The Tiwi Group produced 42,150 carbon credit units in their first year.

“It enables them to gets out to country and buy equipment, having that supports is really hopeful,” explained Willy. The Indigenous Land and Sea Council has overseen the Tiwi management diversity program. It wants to see more groups signed up and operating at a level recognized by the Clean Energy Regulator and the relevant land council to be eligible to earn carbon credits.

There are some areas where there is abatement of carbon soils and indigenous capacity is not reached or realized. There are some areas where new methodologies can be developed with desert ecosystems of lower rainfall where offsets could be generated. Perhaps that’s not as much as in with the wetter parts of the country. Since 2012 there are 32 owned and operated Savannah fire projects in Australia. Combined they abate one million tonnes of carbon. This year and they have offset 1.6 million tons of emissions generating $95,000,000 worth of credits that encompasses 3.6 million hectares of country.

There is significant interest from some other countries of similar terrain like Africa, South and North America. Rangers from Arnhem Land travelled to Botswana, California as well as the Kimberly to talk with the people who are interested and share knowledge.

Unseasonal rain in May and June made for the worst conditions for fire season that the Tiwi Islands have had for the last 12 years. Rangers did their best to protect assets and minimize the impact on carbon emissions. But the environmental impact and comes in different forms. Riders have been part of a program that monitors how fires have affected nationally endangered species in uncontrolled fires.

They have been blamed for the decrease in small mammal species in the Northern Territory in the past three decades. The Charles Darwin University is monitoring the program to see if the Tiwi control burning program improves the outlook for the threatened species. The rangers are impressed to hear their work looks to improve the country. 300 traps are set to catch animals that year for ear-tagging. Results are proving that the cool fire controls are improving the small animal numbers, including the northern brown and common coloured possum.

“In general it is about keeping the country healthy. I want to see the possums and bandicoots for years to come,” said Willy.

“The indigenous program here produced some 7% of Australia’s carbon credits; the system added some $25,000,000 per year. There is room to generate more credits and demand a higher price.” Joi Morrison, of the Indigenous Land and Sea Council points out. “Harness that connectivity of knowledge, indigenous people are very well placed to put a premium price on credits. This is not just about carbon, this is about knowledge, 5000 years of connectivity and importantly this is about ancient knowledge to instil in future generations.”

Willy Rioli, “Wants to see a woman’s ranger group and would support it.”

The A.W.U. wants a minimum wage for seasonal agricultural workers. Farmers prefer the piece-rates as an incentive to work quickly and productively. The evidence arises of exploitation of unskilled foreign workers without any legal representation.

Australia has refused the part of the pledge to reduce methane emissions at the Glasgow’s UNCCC summit.

It is considered to be one of the most potent greenhouse gases and the biggest contributor to global warming behind CO2. But methane accounts for about half of Australia’s emissions from livestock.

Rachel Kyte, UN climate adviser states, “If we can cut the methane emissions by 2030 we take off the acceleration of global warming away. Why Australia is not part of that beats me.” More than 100 countries signed up while Australia sided with Russia, China, India and Iran some of the biggest global emitters. 40 countries signed up to phase out coal for electricity including the major coal issuing countries like Indonesia. Some of the world’s biggest coal producing economies like the U.S., India, China and Australia were missing in the deal.

Tasmanian couple producing Red Wagyu beef go up and beyond carbon positive.

“We need ruminants in grazing to store carbon”

Aiming to sequester more carbon then their beef cattle operation emits. They are using soil and hungry cattle to take CO2 out of the air. Sam and Steph Trethewey bought these 175 hectares farm near Deloraine in northern Tasmania two years ago. Good soils and reliable rain meant they could easily continue rearing cattle conventionally. Climate change concerns of the Sedge to regenerative farming practices. With a three year old and a 12 month baby “What is it going to look like to them?” Steph asked.

They use mass fodder plantings for the climate friendly formula to remove CO2 from the air and sequester it into the soil. That carbon improves the soil to grow more plants.

“I think regenerative practices of a massive opportunity and they are key enabler to store more carbon back in your soils. It is the future and that is something we absolutely have to do, … the agriculture sector can make a difference,” says Sam. They did that to their own greenhouse friendly grass fed beef brand. The bulls are relatively unknown Red Wagyu.

“They marble on long grass, and looking at the data from the Wagyu Association they have up to 20% higher growth rate than the backs [Wagyus].” They are countering the industries’ bad press by assuring customers that, ‘eating red meat is not bad for the planet.’ Their story is that cows are part of the solution. “Cattle have been portrayed as climate villains because of the methane emitting burps. On a beef only enterprise it can be 70% of the greenhouse gas total load. Beef production in the U.S. is the new oil. The industry is finding its feet and talking back as to what it is to those allegations. I believe regeneration practices are agriculture’s answer to the climate crisis. That is because this practice needs short bursts of high intensity grazing. We need ruminants to store carbon and that flips the whole argument on its head. We need the cows to eat the top of the plants to regenerate that growth and turbo-charge the soil with the plants.” Sam explained.

Australia’s red meat industry has set a target to be carbon neutral by 2030. Sam and Steph plan to exceed that, “When you look at the enormous challenge to curb the climate of the planet. Carbon neutral is not good enough, we’ve got to be a net positive, the extra mile.” Can you get there? And how quickly? “We’re hoping in the next 12 months to be honest.”

The Tretheweys in 2019 were the first Tasmanian farmers to register a soil carbon project with Net Emissions Reduction Fund(ERF). To establish base line numbers, core samples were taken across the property down to a metre. It is the most accurate method and the most expensive. It is the only acceptable measuring technique under the protocol of the U.N. Paris agreement. “We decide to go with it because it is the most accepted and the most rigorous method. We can build our brand with it. When we stand up talking about how we tested for carbon we wanted a system we can back it up with, no one can question, its at the top of its game,” said Steph. As carbon credits mature, carbon credits that are worth around $20.00 a tonne now, need to rise. Sam believes theirs will be sort after. The cheaper third party not so verified credits, not audited they will be on the voluntary markets and will not attract a premium. Theirs will be more robust and will be in high demand.

Assoc. Professor Matthew Harrison of the Tasmanian Institute of Agriculture says, “The main way the Tasmanian farmer can gain income from carbon farming is simply through good practice. Carbon farming results in improved sustainability which results generally in improved productivity. Matt is known internationally for his work in climate change adaptation and greenhouse mitigation in agriculture. He warns that some carbon emission reductions schemes in Australia are flaky. You’re getting observations of stored carbon figures from virtual satellite measurements. When they are grounded with traditional agronomic advice from agricultural science you can see through those estimates of the potential carbon sequestration seen through that satellite is unrealistic.”

Botanist Robyn Tait was hired to speed up carbon building’s simple formula, grow as many plants as possible. Plants suck up CO2 and make sugar which feed the fungi and bacteria who make humus and organic matter in the soil and that stores the carbon down there. The seed varieties that they use look like muesli. A summer mix with 23 seed varieties Sam and Robyn sat the soil has already improved with soil moisture and fertility.

Brian Morice worked on the property for 40 years regularly spreading fertilizer. “ I thought they would be here for short time, and they will be gone, because it was totally against what I was taught, now it is going to work. Before I was giving them six months. Seeding multi varieties six months ago and you dig down now and you find roots at1/2 metre deep. You think well something is doing it.”

They launched ‘Tas Agco Beef’ this year. It started with a dream to produce carbon positive beef. In the post Climate conference in Glasgow world beef producers fear being penalized by the export customers of being unable to prove they are de-carbonizing the industry.

This is why key industry figures have visited Deloraine. It might be a shaky start-up producing just three carcasses of a week, but it valley can easily scale up. They are buying properties and building the herd to 2000 head. The key customer is ethical, humane and sustainable and now asking about concerns that are voiced to city butchers about climate impacts. The commercial butchers are proud to be stocking climate mitigating friendly products and understand what they are trying to do.

While Sam and Steph say soil carbon will get them to their net positive target, they also want to decrease emissions from their cattle. They are participating in the methane inhibiting red seaweed feeding trial. Matthew Harrison’s team will trial half of the Trethewey’s herd on bio-char and the other on methane inhibiting sea weed. In the meantime there’s a debate as to how much carbon can be stored in the soil, some say ‘huge amounts,’ others ‘wildly overstated.’ Traditionally thought to be a very slow progress but actually it is a quick process and we can add an inch to soil in a couple of years,” said Robyn Tait. “We need to do this in scale and we need to get bigger producers doing this in a big way,” says Steph Trethewey.

Australian carbon prices are traditionally low compared to those internationally. Like the value of most commodities that has gone up. E. U. Futures are going beyond $100 per tonne. Only $20 a tonne purchased through the Federal government’s ERF. New Zealand and the EU have driven up prices by the government policy. The higher the target the government sets itself the higher the price the market will attract. Dr. Tim Moore of Regenco, natural capital specialists says demand will come from companies who have high carbon futures obligation or higher emission’s targeting policy. Bi-lateral arrangements offer possibilities for markets with Australia and Indonesia or New Zealand or Papua New Guinea: volume is the key, big market demand. Grain is being rationed in overseas countries, bad weather is hitting production areas and Russia has put quota on fertilizer exports.

Further Reading

Victorian winery on track to be carbon neutral without offsets by 2025

ABC news Reporter: Billy Draper

Tahbilk is situated on the traditional lands of the Taungurung people and was established as a winery in 1860. On the banks of the of the Goulburn River in north-east Victoria, is one of the few vineyards in Australia to be certified as fully carbon neutral.

The operation near Nagambie, where Hayley Purbrick’s family has been making wine for five generations, offsets all the carbon dioxide it creates.

The winery’s journey to becoming carbon neutral began in 1998, when trees were planted to revegetate the property, and in 2008 it undertook its first carbon audit to start looking at ways to lower its carbon footprint.

“It’s just the right thing to do,” Ms Purbrick said.

“I think if you’re a business and you’re not doing these types of things then you’re missing out on the future of the next generation.”

Over the past decade, the business has reduced carbon emissions by 45 per cent by using solar power, revegetating areas and using heat-reflective paint on its restaurant roof.

“They use it on rocket ships,” Ms Purbrick said.

Key points

- 120 hectares of land has been revegetated

- The winery offsets 97 per cent of its emissions without buying carbon credits

- Since 2008 it has reduced emissions by 45 per cent through carbon auditing

Nature-Based Global Emissions Offset™ is an evolution of CBL’s Global Emissions Offset. The N-GEO™ provides companies with a streamlined way to meet emissions-reductions targets using offsets sourced exclusively from Agriculture, Forestry, and Other Land Use (AFOLU) projects. Xpansiv – CBL

Air capture machines suck carbon dioxide from the atmosphere.

Are they part of the solution?

ABC Science By technology reporter James Purtill

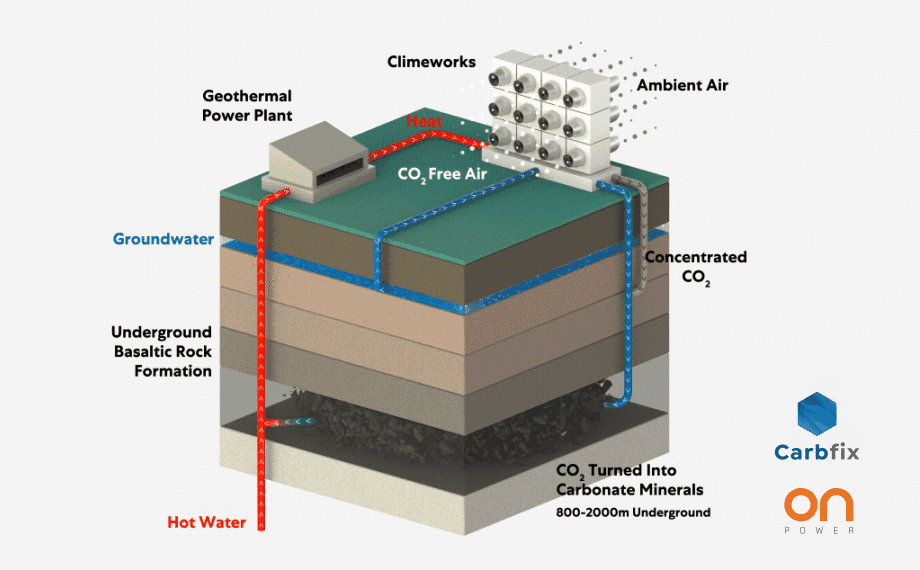

On a barren lava plateau in Iceland stands an entirely new kind of industrial facility that sucks carbon dioxide from the air and traps it in stone.

The world’s first commercial direct air capture (DAC) plant is designed to remove thousands of tonnes of greenhouse gas every year and then inject it deep underground.

These first plants are coming online, with the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) recognizing that, even if the world reduces its ongoing emissions as quickly as possible, there will still be too much CO2 in the atmosphere to avoid catastrophic levels of global warming. The world needs to both reduce future emissions and remove historical ones to reach a safe climate.

Why not just plant more trees?

When Deanna D’Alessandro, a professor of chemistry at the University of Sydney, encountered the idea of mechanical carbon removal, she wondered if there wasn’t a simpler solution.

A tree, of course, is a pre-existing and relatively cheap technology that sequesters CO2 in wood and other biomass.

When scaled up, it’s called a forest.

When Deanna D’Alessandro, a professor of chemistry at the University of Sydney, encountered the idea of mechanical carbon removal, she wondered if there wasn’t a simpler solution.

A tree, of course, is a pre-existing and relatively cheap technology that sequesters CO2 in wood and other biomass.

When scaled up, it’s called a forest.

“My first thought was why not plant more trees,” Professor D’Alessandro said.

“And then I did the numbers and stood in awe of them.”

By her own calculations, using reforesting to capture Australia’s CO2 emissions for two years (about 1 billion tonnes), would require an area of land equivalent to the size of New South Wales.

DAC could do the same with 99.7 per cent less space, she said.

“Not only do we not have the land, we don’t have the water to achieve natural sequestration.”

Mark Howden, director of the Climate Change Institute at the Australian National University, agrees.

“The science is very clear that to keep temperatures down to [an increase of] 1.5C, we not only need to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, we also have to absorb CO2 from the atmosphere,” he said.

“It’s increasingly clear that doing that just from planting trees and relying on farmers and soil carbon is not enough.”

How does direct air capture work?

DAC is just one of several proposed technologies designed to remove emissions from the atmosphere, which also include repurposing offshore oil and gas platforms to grow seaweed and turn it into fire-resilient bricks.

So, DAC works a little bit like a household dehumidifier, but instead of stripping water out of the air, it removes carbon dioxide.

The greatest challenge, says Professor D’Alessandro, is processing enough air to capture a significant amount of CO2, given the gas makes up just 0.04 per cent of the air we breathe.

“To be frank, it’s been one of the most interesting scientific problems in chemistry in the past 10 years,” Professor D’Alessandro said.

There are generally two approaches.

In the first, a fan pulls air into a structure lined with thin plastic surfaces that have potassium hydroxide solution flowing over them.

The solution chemically binds with the CO2 molecules, removing them from the air and trapping them in the liquid solution as a carbonate salt.

In the second method, a sponge-like filter absorbs CO2 and is then reheated to release the gas into storage.

In the case of the plant in Iceland, the captured CO2 is injected about a kilometre underground into volcanic rock.

Over two years, it reacts with the basalt to form a solid carbonate material.

But underground storage isn’t the only option, Professor Howden said.

“Probably the dumbest thing we can do with captured CO2 is put it in the ground,” he said.

“To my mind, if we’ve gone to the bother of capturing CO2, why not treat it as a resource?”

Another DAC company, Canada’s Carbon Engineering, plans to use captured CO2 as an input to make carbon-neutral synthetic fuels that can substitute for diesel, petrol or jet fuel.

Other proposals include using CO2 in cement production and plastics manufacturing, which could make buildings and water bottles carbon negative.

Is this any different to carbon capture and storage?

CCS involves capturing CO2 at the site of production, such as a gas liquefaction plant or coal-fired power station, and then pumping it deep underground.

Instead of filtering the air, it filters emissions from a smokestack.

Although the Australian government has singled CCS out as a priority technology for emissions reduction, critics have said it’s a failure.

One of the major problems is CO2 leaking from underground reservoirs.

With DAC, there’s a much lower risk of leakage, Professor Howden said.

“With standard CCS you’re restricted in the geology to somewhere close to the point of combustion, whereas you can put a DAC system anywhere, so you find geology that’s suitable and locate it there.”

How much CO2 needs to be captured?

DAC would need to be enormously scaled up to be useful.

Even if the world reaches net zero by 2050, it will still be necessary to remove 5 to 14 billion tonnes of CO2 per year from the atmosphere from 2030 onwards to keep global warming below the 1.5C limit set by the Paris Agreement, according to a University of Melbourne report.

The DAC plant in Iceland, which is the world’s biggest, can capture and remove 4,000 metric tonnes of CO2 a year.

That’s about 10 million times less than annual global emissions.

At our current level of emissions, humanity is cancelling out the plant’s yearly efforts every three seconds.